It’s 12:15 p.m. on Saturday Oct. 22 and there’s not a soul in sight.

I didn’t expect there to be too many people around but it is only October and it’s a surprisingly pleasant day in southeastern South Dakota — I thought there might be at least one other person out here. Everyone must be out pheasant hunting.

I’ve made the nearly two hour drive on Highway 34 west to Pony Hills Country Club, located just outside of exotic Woonsocket, South Dakota. The course is lowkey and doesn’t always appear on iPhone Maps. To get there, you have to kind of know where to go (straight west of town for about three miles).

Pony Hills isn’t really anything too special — it’s not on any lists for best courses in South Dakota, nor does it have any “must play” holes. The South Dakota Golf Association doesn’t even list it in its course directory. It does have one unique feature that is nearly extinct in golf today: Sand greens.

Now, I’m not talking sand based greens — which are common in South Dakota — I’m talking literal sand greens. Once the norm in courses around the region, sand greens are all but extinct. To my knowledge, Pony Hills and May Acres (located in Selby) are the only two golf courses with sand greens in the state. A true relic of the past, I had to experience them for myself.

When you get to the course, you can’t help but feel like you’re transported back in time. It oozes that “forgotten about since the ‘90s” feel — similar to what Prairie Lanes (the Brookings bowling alley) felt like before the recent remodel. The Pony Hill’s sign is weathered and chipping paint, the clubhouse is locked with a sign reading “Winterized for the year” which might as well say “play at your own risk.” Green fees are $10 and rely on the honor system — I slid a Hamilton into the clubhouse through a wooden shaft.

Pony Hills kicks off with a short, 260-yard par 4. The tee box is a patch of artificial turf next to the sign. Looking up towards the hole, there is no way to separate fairway from rough — just a sea of yellowed crab grass uphill towards a postage stamp sand green. But I didn’t come here to complain about playing conditions or analyze the course layout, I came here to figure out what sand greens are like.

In the very early days of golf in the United States, grass greens were very rare. Irrigation was limited and expensive, and most attempts at grass greens failed. To combat the limited water supply while still being able to play the game, sand greens were invented and became the norm around most of the entire country, aside from the northeast. Even the fabled Pinehurst Golf Resort, home to one of the world’s most celebrated golf courses (#2), had sand greens until 1934.

Sand greens were developed by simply digging a six to eight foot cavity and filling in the top with your standard run-of-the-mill sand. Then, to keep the sand from blowing away, motor oil was dumped on top. This created a heavier, more binding sand which also prevented insects from burrowing or plants from growing. Sand greens were especially popular in places prone to drought and dotted the plains of Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota and parts of Canada. In fact, the first golf course in Brookings, the Brookings Country Club, had sand greens until the 1940s. The BCC was established in 1921 after a group of young men, Horace and Van Fishback, Elmer Sexauer, Earl Bartling and others, leased 50 acres of land from A.J. Kendall. Originally just a pasture with nine tomato cans as holes, the course was designed and developed, adding in sand greens and a clubhouse by 1926.

In a 1960 letter to the BCC, Ed Betty wrote: “8 foot greens with sand and oil — quite a change from what you have now.”

The BCC wasn’t the only course in Brookings that had sand greens. Another course became established around the early 1950s, located just north of town, where the community gardens are now. The course had a handful of names and — from my own research over the last few months — has largely been forgotten.

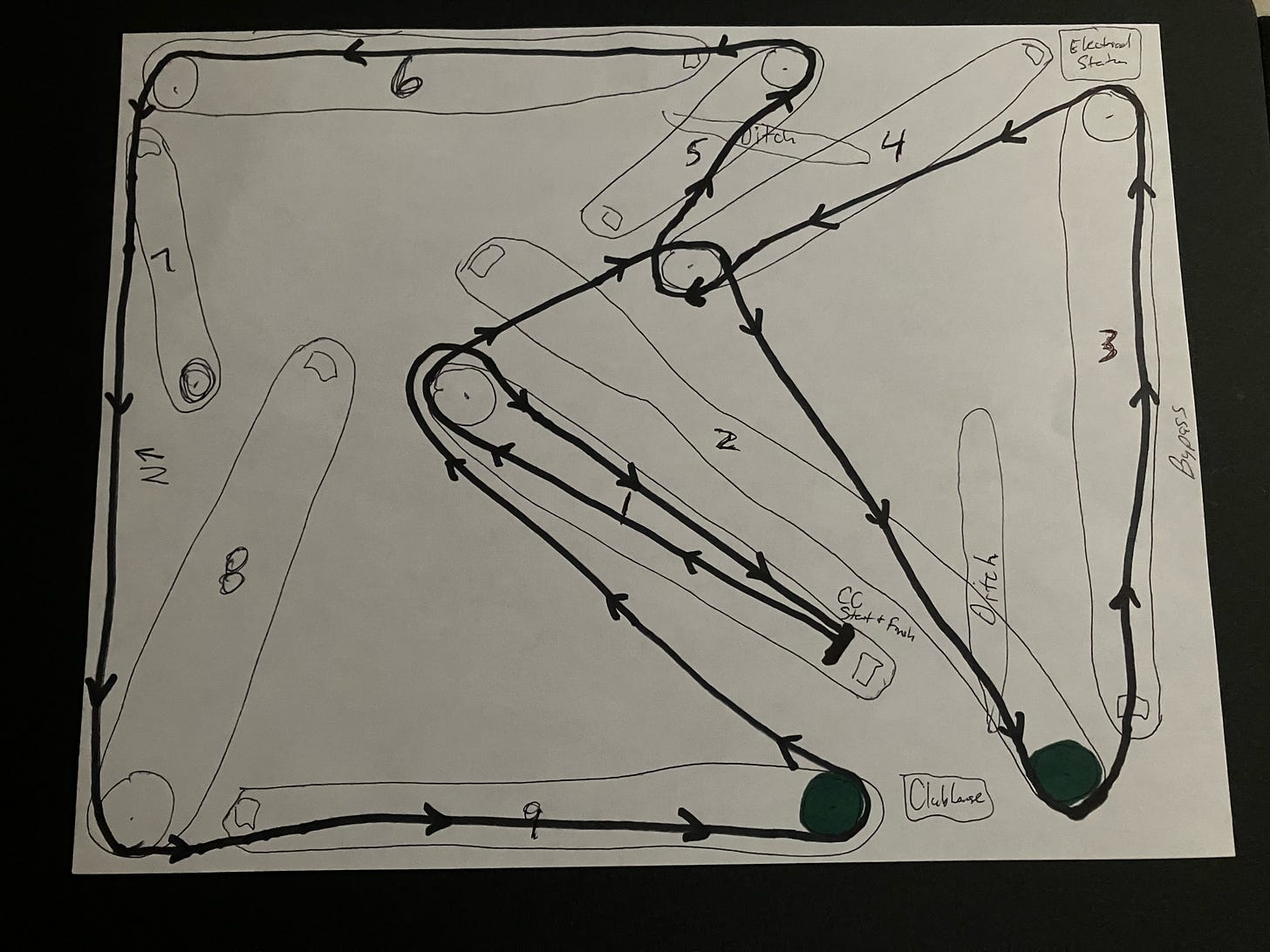

The North Course, the South Dakota State University course, the Blue and Yellow course — whatever people referred to it by — was established at some point in the last 1940s or early 1950s. It was a nine hole course, with seven sand greens and two grass greens. This is the first time that I had ever heard of a “combination” course. Why was there a mix of the two styles of greens?

“From what I remember, it was because the water hose from the clubhouse could only reach to two holes,” said Dick Bartling, a Brookings native who played on the course in his youth.

Whenever the #2 and #9 greens needed to be watered, the maintenance guy, often a student at South Dakota State College (now University), would drag a water hose attached to a sprinkler out to the greens, let it run for the bit, and then drag it to the other hole—an incredibly high tech irrigation system.

Like most sand green courses, it was very low maintenance and very affordable.

“As a kid, I remember going out there to the North Course, because it was just so much easier to go to (compared to the BCC),” Bartling said. “You could just ride your bike out there and carry your clubs.”

My drive on #1 was a weak three wood that started right and went even more right. Approaching the first sand green, it became clear the biggest challenge was the actual size of the greens. All nine at Pony Hills were the same size—no more than 10 ft. across either side—with the cup directly in the center. My second shot landed just right of the green, in what would be the fringe if this were a grass green. I figured that the way to play these kind of shots would to do the ole “bump and run,” leaving a few feet for par. Maybe the sand was especially loose on this day and the greenskeeper forgot to mix in the motor oil from his ’76 Chevy, because after the “bump,” the ball just died, rather than “running.”

This left about five feet to clean up for par. For putts on a sand green, you first must smooth a path for yourself using the rake that sits near the hole. I wasn’t exactly sure what the proper rules for marking the ball were, so I did the classic tee-in-the-ground and blazed a trail from tee to cup.

Here’s a rule of thumb when you’re playing the sand: when in doubt, hammer the putt. Unless you absolutely crank it, there’s a very good chance the ball will settle no more than a foot or two past the hole. Second, with no break, no elevation (sand greens are basically all flat), there’s really not a risk in missing badly. The unsmoothed part that borders part of your putting path, and the unsmooth part behind the hole will keep things from going south. The only thing you can really do to screw up on the greens is leave it short. Unsurprisingly, I left the putt way short.

The manual labor continued after I cleaned up for bogey. To “fix” the green, you take, in this case, an old, heavy rake that most people probably associate with gardening. Starting directly next to the hole, you drag the rake behind you as you walk in a circular, motion, gradually moving all the way around the hole and then around the rest of the green. Between smoothing, putting, and raking, this first hole took me much longer than I care to admit. Slow play is my biggest pet peeve (not just in golf, but in life) and I can’t imagine how slow things can get when the course is full.

Located at the northeast intersection of Highway 14 Bypass and Medary Ave., the North Course was originally owned by the City of Brookings and operated by the local American Legion. It wasn’t until the mid 1950s that the Physical Education Department at SDSC took over its management. The April 9, 1956 edition of the Argus Leader remembers the changeover:

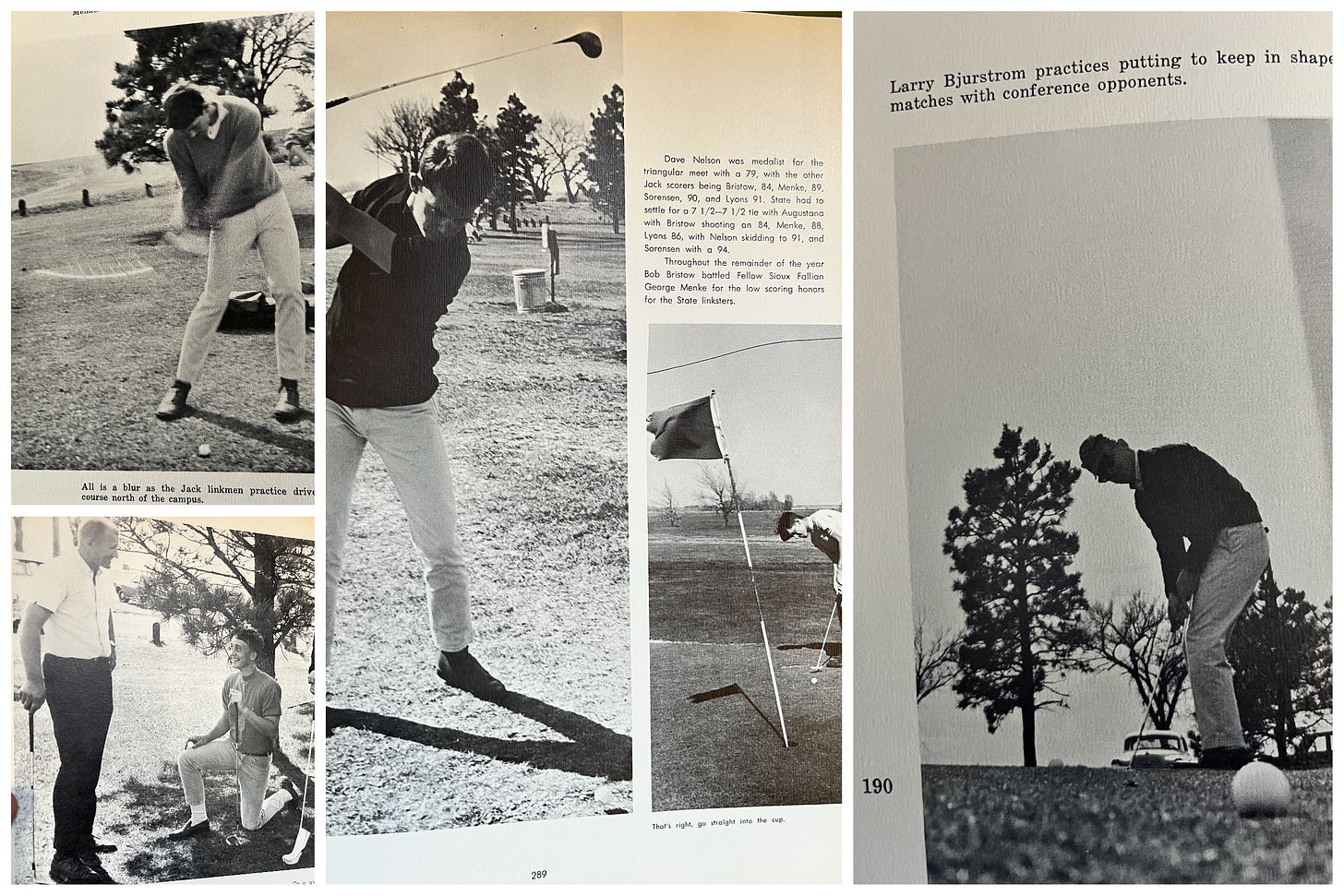

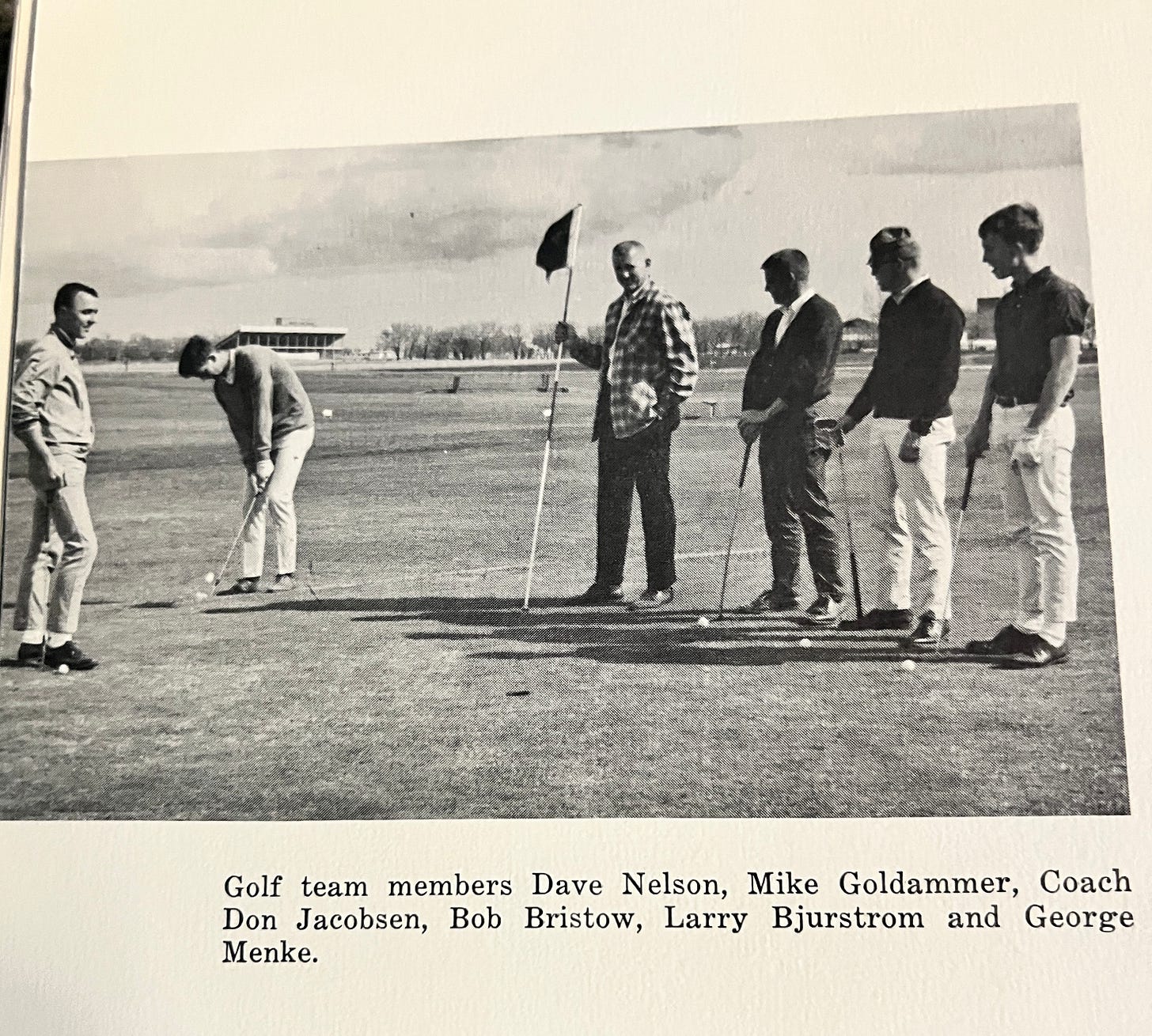

Of note, the varsity golf and cross country teams used the course for practice. The first manager of the course was Lawrence (Bubb) Korver, the 1955 co-captain of the football team, who had “previous experience in golf course management in his hometown of Orange City, Iowa.”

Those who played the North Course remember it as a rather standard small-town golf course from that era. The environment was very casual and relaxed. It cost no more than $1 a round and that was only if someone was manning the small maintenance building that doubled as a clubhouse. In 1955, a family membership to the North Course would run about $10 ($111 factoring in today’s inflation).

“Rarely was there anybody in the clubhouse,” said Pat Lockwood, a Brookings native who played on the course in his youth. “Quite often there wasn’t even anybody there to take your money. There was a slot in the door and you’d drop your money in the can to play.”

If you venture out to the community gardens now, you’ll see quite a few trees but in the course’s heyday, it was wide open. The fairways didn’t have an irrigation system and relied solely on rain. Firm conditions were the norm during July and August.

“They mowed everything down pretty tight,” Lockwood said. “The sand greens were very small.”

Like Pony Hills, all the greens were dead flat, with the cup and flagstick directly in the center. Each of the sand greens had a substantial amount of oil added to them, to ensure things stayed relatively firm and the sand wouldn’t blow away.

“They dumped whatever they had into the sand—motor oil, diesel fuel, things like that,” Bartling said. “It would rain and that stuff would soak down into the ground. In that era, there wasn’t a lot of environmental protection.”

The course, which was a par 36, was relatively short in terms of yardage.

“I mean they were all generally pretty short,” Lockwood said. “Nothing was very long. There was two par fives, the second and the sixth.”

Lockwood remembers that even with the equipment back then, reaching the par fives in two shots was common. Of course, that is Lockwood saying that, a guy who was inducted into the South Dakota Golf Hall of Fame in 2011 and was the SDGA Men’s Amateur Champion in 1981 and 1998. He also played college golf at the University of Missouri and SDSU, before returning to Brookings where he won 12 BCC titles and 10 city championships.

The North Course is where Lockwood broke par at for the first time. At age 11, he shot a one under 35.

Some of South Dakota’s greatest golfers played at the North Course, including Lockwood, Steve Jansa (SDGA Class of 2017), Lorne Bartling (SDGA Class of 1985), and many, many others.

Jansa, who played basketball at SDSC for one year before transferring to Creighton University, aced the 318-yard par 4 third hole on April 29, 1965. According to the Argus Leader, it was Jansa’s first time playing that season and he used a driver. The hole-in-one was witnessed by Tom Timpone, Denny Dee, Mike Roach and Lloyd Wilson.

“You know, I’ve always had a question in the back of my mind whether it really happened or not,” Jansa explained. “I know I drove the ball and it went towards the green, and the guys were up at the green and I didn’t get a huge reaction from them at the time, but when I got up there, the ball was in the hole. I have always had a little bit of suspicion that they might have put it in there. I don’t have any proof one way or the other.”

Thankfully, Jansa has had a few more aces since he last played the North Course. After completing a solid career at Creighton, the 6-7 Jansa returned to South Dakota, where he was a championship-level amateur, winning the SDGA Pre-Senior Tournament in 1986 and the SDGA Senior Tournament in 2002. His son, Ryan, is one of the most decorated golfers in South Dakota history.

Lawrence (“Lorne” ,“Bones”) Bartling (Earl’s son, Bob’s brother and Dick’s father) was one of the area’s greatest athletes, helping the Brookings High School Bobcats to conference and state titles in golf and basketball. After graduating from BHS in 1933, Lorne played basketball at SDSC, while also continuing with amateur golf. Some of Lorne’s career highlights include qualifying for the SDGA Match Play Championship 36 years in a row and winning nine BCC Club Championships.

Lorne frequented the North Course, often in the mornings, to get extra practice in. Rather than drive out to Lake Campbell, he would make the short trip just north of town. Unlike the BCC, the North Course did not have a driving range so Lorne would bring a sack of balls, dump then in the middle of one of the fairways and swing away. To quickly retrieve the balls, Lorne devised a pickup tool out of a metal wire and an old golf shaft.

“The bottom line is, he loved to practice and rather than drive all the way to the country club, he would go hit balls out there at 6 a.m. before he went to go work at the furniture store,” Dick explained. “That’s where he really honed his game.”

It’s also the place where Lorne found a new passion. It was 1969 and Lorne’s father, Earl, has just passed away from a heart attack.

“He’s out there hitting balls one morning and he decides he’s going to see if he can run to where he hit his drives to,” Dick said. “He was a great athlete but had never run a step in his life. He’s starts jogging out to where the balls were and he can’t run 240 yards without getting out of breath. But then all of sudden from that point on—just like Forrest Gump—he just felt like running.”

Lorne completely “gave up” on competitive golf and started running nearly everyday. Him and his brother, Bob, and a gaggle of SDSU professors would hit the streets of Brookings at 6 a.m. for morning runs. They eventually co-founded Prairie Striders, a running club that continues to this day. Lorne and Bob also decided to start selling running shoes out of their family owned furniture store. At first, they sold ASICS, a popular brand out of Japan, and then Bob decided to start selling shoes from a little known company out of Oregon—Blue Ribbon Sports. Of course, Blue Ribbon Sports would eventually morph into the megabrand Nike. The Bartlings were the first in the state (and probably the Upper Midwest) to sell Nike shoes.

“I actually had the first pair of Nike basketball shoes in the state of South Dakota,” Dick recalled.

Lorne’s passion for running continued to grow and by 1983, he had logged 25,000 miles—enough to circle the globe. He set various national age group records and was an ardent supporter of both golf and running in South Dakota. He passed away in 2009 at the age of 94.

By the 5th green, the novelty of sand golf had worn off. After the fourth smooth, putt, rake combination, it became overwhelmingly clear why sand golf has largely disappeared. It was also clear why sand golf still persists in parts of Canada. The maintenance required is so minimal that weather isn’t even much of a concern.

My only complaint about Pony Hills was that sometimes the layout was not very clear. For example, the fourth hole is an uphill par 4, with two flagsticks visible from the teebox. From my perspective, it seemed as though the correct 4th hole layout could have been to either of the flagsticks but I thought it was more than likely the flag that was slightly to the right (of the teebox) was the correct layout. I took a healthy swing with the three wood and sent the ball tracking toward the green (probably the “best” shot of the day). After a bounce on an upslope, the ball seemed to settle on the green but because of a bush, it wasn’t visible. I got up to the hole and the ball was maybe 3 ft. from the cup. I immediately got out my phone and started to see if there was any “sand golf tournaments” coming up in the area. Unfortunately, after I looked around for a moment, it became overwhelming clear that I had aimed at the wrong green. So the “good shot” was nearly a “black ace” that actually resulted in a double bogey. Just ridiculous golf.

Most of the holes at Pony Hills fell in that 200-350 yard range and all of them would have been considerably more challenging on a windy day. The most interesting of them all was the 8th, which was a short-ish uphill par three. Off the tee, you have to “thread the needle” and navigate an overhanging power line.

I ended the round at Pony Hills unspectacularly, with a par. By the ninth hole, I had already come to my final verdict on sand greens: An interesting experience that is reflective of a bygone era. Sand golf is unique, but as I found out, unique does not always equal enjoyable. Still, for those interested in the history of the game, a round of sand golf has to be on the to-do list.

The North Course had a solid 20-year run but by the early 1970s, it was clear the course was on its way out. The City of Brookings aquired land at 22nd Ave. South in 1968, with plans for a new, nine hole all grass greens golf course.

With the help of Lorne, the city designed and constructed Edgebrook Golf Course. By the spring of 1973, Edgebrook was operational and plans to turn the North Course into a community garden area were in motion.

For almost everyone, the North Course is merely a distant memory. The few that do recall the course remember it for its accessibility and low maintenance. Others remember it as the host of the South Dakota High School Cross Country Championships for the entirety of the 1960s and the early part of the 70s. Regardless, the North Course served its purpose: a cheap, accessible way for the community to play and learn the game of golf—something that I think would be welcomed in this pandemic fueled golf boom that we are seeing today.

*I originally intended to send this out on Monday morning this week but I couldn’t figure out how I wanted to end this story (which is already a little too long). Originally, I thought some sort of sentimental reflection on the course/sand golf would be appropriate but it just didn’t feel right. So I’ll end it with this note and a thank you to Dick Bartling, Pat Lockwood, Steve Jansa, Chuck Cecil and Dave Graves for their help/cooperation on this story. When I first heard about “the Blue and Yellow” golf course sitting at Cubby’s last April, I was immediately interested in writing some sort of story on the course/its history. While I’m not completely satisfied in how this turned out, I’m glad it was able to finally get over the finish line. Thanks for reading - Addison

I ran cross country on the SDSU course in the 1950's. We did most of our training there and had a race or two. I remember a dual meet with the University of Minnesota in 1958.

Great story. The last year of the State Cross Country meet being held at the North course was 1975. I ran that year as a sophomore at Lincoln High School. The distance was 2.2 miles. The next year, with distance going metric to 5000 meters, the location was moved to Edgebrook.