Return of the Sturgeon

A "living dinosaur" returns to South Dakota's waters in this conservation success story

The old timers at Big Stone Lake had all the best stories, Norm Haukos said.

Haukos' father had been a commercial fisherman on the 26-mile Minnesota-South Dakota border lake. He grew up hearing stories of the lake's prehistoric monsters and saw pictures of giant lake sturgeon — some over 10 feet in length and weighing well over 100 pounds — adorned along the walls of cabins and local watering holes.

But Haukos never had the chance to see a Big Stone sturgeon in the flesh as the last one washed up on the lake’s shores in 1938.

This long, slender fish, with its cartilaginous structure, is considered one of the closest living relatives to dinosaurs. According to fossil records, sturgeon have been on Earth for at least one hundred fifty million years, dating as far back as the Triassic Period, and their biology has remained more or less the same.

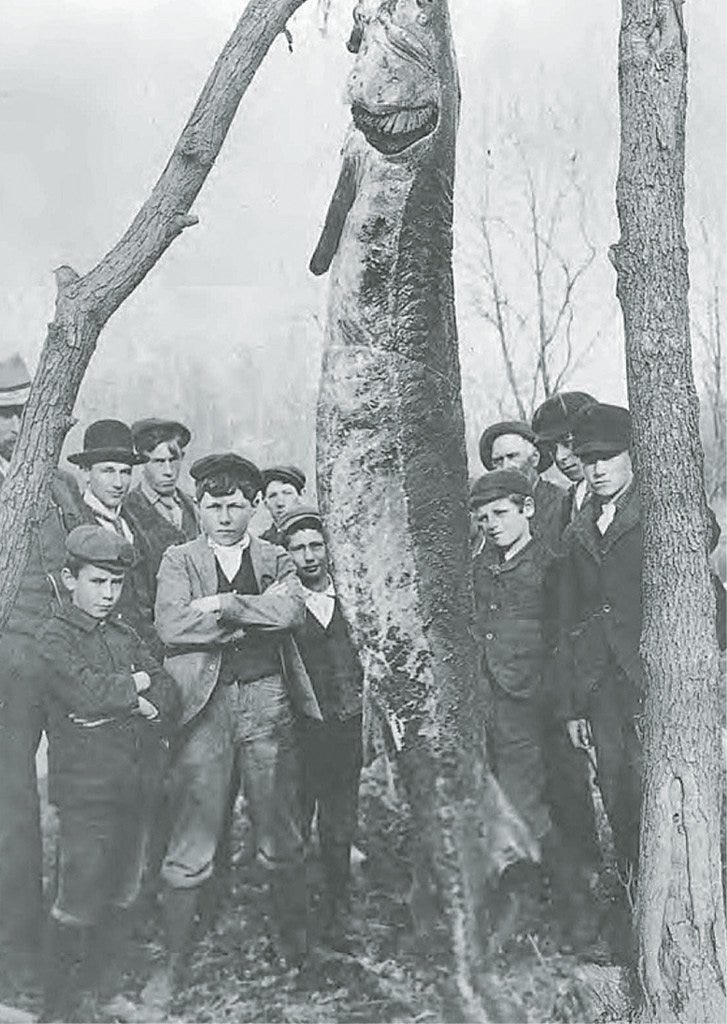

Sturgeon were once abundant in Big Stone Lake. In fact, sturgeon could be found in most lakes and rivers in the Upper Midwest. But in the 1800s, settlers from the east moved into the region and began commercial fishing. Sturgeon were originally considered a nuisance fish as their boney body would cut through fishing nets.

Like other pests, they were hunted — so much so they were stacked on shorelines like logs. Eventually, fisherman realized sturgeon meat had high oil content and began burning them as fuel to power steam ships.

By the late 1800s, caviar became increasingly popular in Europe and sturgeon were harvested relentlessly for their roe — a delicacy similar to caviar. Soon, overfishing completely collapsed the country’s sturgeon population. By the 1960s, the prehistoric fish was a distant memory at Big Stone.

In the 1880s, it was estimated that over 4 million pounds of sturgeon were taken from Lake Huron and processed in the state of Michigan. By 1928, the total sturgeon harvest from all of the Great Lakes was less than 2,000 pounds.

When Haukos became the Ortonville fisheries supervisor in 2001, he had a vision of bringing back Big Stone's sturgeon population. One of the first things he began looking at was habitat. Was Big Stone even suitable for sturgeon anymore?

Water quality was at the top of mind for Haukos. Big Stone had its fair share of water issues and its quality had dropped signficantly throughout the 1900s. In the 1960s, according to Haukos, there were even a number of communities dumping sewage into the lake.

"That really raised havoc with the water quality," Haukos said.

But by the 1980s and 1990s, federal programs worked to improve the lake's water quality. Silt flowing into the lake was reduced and homeowners learned of ways to reduce phosphorus pollution. By the early 2000s, Big Stone's water quality had improved significantly.

While overharvesting and, to a lesser extent, lake pollution contributed to the sturgeon’s demise, dam construction on many of the rivers and tributaries surrounding Big Stone played a considerable factor in the fish's downfall. When sturgeon spawn, they will swim upstream to shallow creeks and rapids. The construction of dams prevented sturgeon from reaching their preferred spawning grounds and because female sturgeon take at least 20 years to reach sexual maturity, their population growth all but halted.

The average life span for a lake sturgeon is between 50 and 60 years but it is common for them to exceed this. Century-old sturgeon are fairly common and there are reports of females living up to 150 years.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources worked with various groups to remove dams at Minnesota Falls, Pomme de Terre and Lac qui Parle. Some of the other dams were converted into sloping rapids, allowing passage for sturgeon and other fish.

The improved water quality, coupled with accessible spawning habitat, made a sturgeon reintroduction much more feasible.

"All of the things that were improved upon actually led to the demise of the lake sturgeon," Haukos noted.

While the state of Minnesota had developed sturgeon management plans in the early 1990s, Haukos made his first proposal in St. Paul for a sturgeon reintroduction at Big Stone around 2003. While the proposal was shot down, it provided Haukos valuable insight.

"We didn't give up on it," Haukos said.

One of the biggest questions surrounding the sturgeon reintroduction was genetics. Minnesota has strict requirements for fish introductions. As North America's sturgeon population had declined precipitously, finding sturgeon that matched the genetics of the original Big Stone population would be a challenge.

Wisconsin has the largest lake sturgeon population in the world and the Genoa National Fish Hatchery, located south of La Crosse on the Mississippi River, had been hatching lake sturgeon for quite a while. Their sturgeon’s genetics, derived from the Mississippi River, matched Big Stone’s. The Genoa Hatchery also had a previous relationship with the state of Minnesota which made meeting the stocking requirements much easier.

Through a joint partnership between Minnesota, South Dakota and the Citizens for Big Stone Lake, Big Stone received their first stocking of 6,500 lake sturgeon fingerlings in 2014. Each of the fingerlings have small tags inserted in them, which allows fisheries staff to track the population and the stocking year. In 2015, another 7,500 fingerlings were stocked and in 2016, an additional 3,600 were released. In total, around 44,500 sturgeon have been stocked at Big Stone.

More than a decade after the initial reintroduction, Big Stone now has a healthy population of sturgeon. Interestingly, Big Stone's sturgeon are growing much faster than other rebounding populations in the state, Huakos said. There have been reports of fish as big as 60 inches caught in nets and there are indications that larger sturgeon are roaming near the bottom of the relatively shallow lake.

Lake sturgeon are bottom feeders and eat a variety of snails, crayfish, mussels and insects. While they will not eat anything larger than a small fish, sturgeon essentially have zero predators — aside from humans — in the water.

Signs of a rebounding population are good enough that last year, a catch-and-release angling season was offered between June and April. The season will resume this year on June 16.

"We know that we have created a lake sturgeon population," Haukos said. "And that is a success in itself."

Watch: Lake sturgeon on the Minnesota River south of Big Stone Lake

While it is not believed that the sturgeon are spawning just quite yet, male sturgeon are migrating upstream to what would be their preferred spawning ground. This is clear sign to Haukos that the sturgeon are well on their way to a self-sustaining population.

"The ultimate success is if we get a naturally reproducing population," Haukos said.

Big Stone isn't the only waterbody with a healthy, growing population in Minnesota. Lake sturgeon can also be found in the Rainy River, the St. Croix River, St. Louis River and Mississippi River. The Rainy River, located in northern Minnesota, boasts the only harvest season in the state — anglers can take one sturgeon per year — which attracts anglers from around the world. As Haukos mentions, a harvest season is possible at Big Stone but that is a long ways down the road.