Rambling about NIL

N – I – L, three letters that have been at the forefront of every conversation involving college athletics for the past year or so. You want to talk about Alabama football? NIL will be mentioned in the first 30 seconds of conversation. You want to talk about a recent transfer? NIL talk will follow in lockstep. Many have said that NIL will be the proverbial nail in the NCAA’s coffin, while others have argued that NIL may ultimately save college athletics. While it may be too early in this ongoing saga to know which inkling is correct, understanding what NIL is—and what it’s not—is crucial to any nuanced conversation about college athletics these days.

“NLI, NIL, NCAA – what the hell does it mean?”

There’s a lot of acronyms in college athletics so let’s get a few of them straight. NCAA stands for National Collegiate Athletic Association, duh. NIL stands for Name, Image and Likeness. SEC stands for Spend Every Cent (I’m half-joking). Now that we got the important acronyms straight, how did this NIL “mess” start?

Like all great things that happen in the United States, the NIL saga began in the courtroom. The door for student-athletes being able to profit off their NIL creaked open in a 2014 antitrust decision, which saw the courts side with former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon. He argued that student-athletes who appear in video games (EA Sports’ NCAA College Football & College Basketball) should get some money, as they were being prominently featured in the games. EA Sports settled with O’Bannon and the many former student-athletes who joined in the suit but the NCAA continued the battle in court, ultimately paying north of $40 million in legal fees. The decision in the O’Bannon vs. NCAA case opened the floodgates for others to challenge the NCAA’s stranglehold on NIL rules.

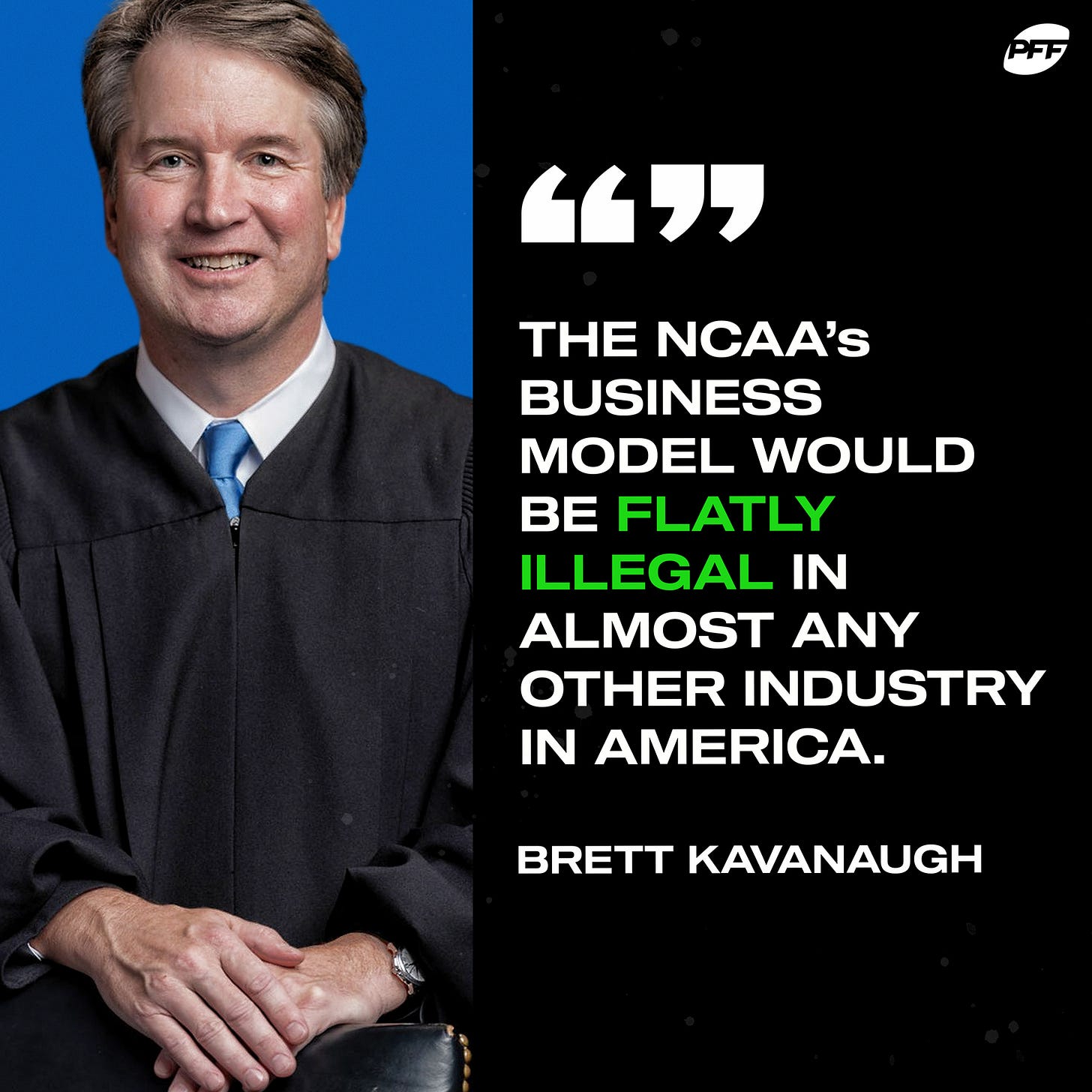

Enter the NCAA vs. Alston—a landmark case that reached the highest court in the land. The basic question being asked: can the NCAA restrict education-related compensation benefits for student-athletes? The Supreme Court unanimously decided with Alston, ruling that the NCAA could not restrict member institutions from offering compensation and benefits for academic achievements and degrees.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh also wrote a scalding concurrence which was highly critical of the NCAA.

“Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate,” Kavanaugh said. “The NCAA is not above the law.”

Legal scholars have said that Kavanuagh’s concurrence is basically inviting the next lawsuit against the NCAA to the front steps of the high court.

At the same time that Alston was being decided, states across the country were passing NIL legislation which allowed student-athletes to benefit from their NIL. In Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine even signed an executive order allowing student-athletes to receive NIL benefits (I wonder if Ohio St’s football program helped him with the paperwork?). Before many of these laws went into place (July 1st, 2021), the NCAA chose to relax many of their NIL rules on June 30. The legislative pressure tied the hands of the NCAA which stated that student-athletes across the country—regardless of whether or not the state had NIL legislation—could profit off their NIL. One glaring caveat—also made clear in the Alston ruling—was that pay-for-play would still be strictly prohibited.

The relaxed NIL rules meant that student-athletes could now endorse things or sign things (among other things), and be compensated for it. For example, former University of Iowa basketball player Jordan Bohannon signed a deal with Boomin Fireworks. While its not specified how much Bohannon is/was making off the deal, he clearly used his large platform to promote the fireworks stand. Probably not what the NCAA envisioned but within the confines of the vague rules set forth.

Further student-athletes could now get paid for autographs or they could put on their own camps. For example, a baseball player at the University of Oklahoma could put on a hitting camp for middle schoolers. Under the current NIL rules, he could make money from the camp and use his NIL to promote it.

Student-athletes could also begin using agents, legally, to create NIL deals and represent their best interests. The NCAA begin loosening their rules on agents in 2018 when they allowed men’s basketball players to use NCAA-certified agents to test the draft waters while retaining their eligibilty.

The new interim rules also made many of the past “conroversies” somewhat laughable. For example, in 2014, Todd Gurley, then a standout running back with the Georgia Bulldogs, had allegedly charged for his signature when signing memorabilia and was suspended four games. If this had happened in the year 2022, it’s a non-story and just another example of a student-athlete utilizing his NIL.

The NIL rules put forth by the NCAA were intentionally loose and vague under the premise that Congress would soon enact federal regulations. Earlier this spring, Greg Sankey, SEC commissioner, and George Kliavkoff, PAC-12 commissioner, met with members of Congress to lobby for federal regulation. Sankey said this about his visit to Congrees at last month’s SEC meetings.

“To have a national standard, it appears to us that Congress has to act. And Congress may opt to not act. If that happens, we’re now in hypothetical land and the [ sic ] question is a relevant one about conference oversight.”

Personally, I am so happy to know that commissioners from two of the largest conferences in the country are lobbying for rules that will apply to all NCAA affiliated institutions. I know Sankey has schools like SDSU in mind!

Until these federal regulations are put in place (I won’t hold my breath), athletic departments will continue to navigate the murky waters that is present day college athletics.

The Wild Wild West

The changes that came from the summer of ’21 were the catalyst for the chaos that were are seeing today. The NIL changes, while not necessarily shocking, were brand new to everyone, regardless of school, conference affiliation, or sport. With little guidance from the NCAA, schools and conferences were basically left to deal with this historic change on their own. Some foresaw the power that NIL was/could be/is; others not so much. Enter Jimbo Fisher and Texas A&M. No school nor program captured the power of NIL as quickly and efficiently as TAMU Football. Let’s think back to a few weeks ago when Alabama Football coach Nick Saban told a room full of big money donors in Birmingham that Texas A&M “had bought all of their players.”

Fisher got all riled up and threw some stones back at Saban. Why? Because it was true. Texas A&M used a group of boosters—what we are now calling a collective—and basically offered up large NIL deals to recruits under the premise that they would come to College Station. This landed them the number 1 recruiting class in the country (ahead of ‘Bama) and the most five-stars in any one class ever—largely considered the best recruiting class (based on stars and rankings) of all time. While TAMU is a solid program in the SEC, ain’t no way they should have landed all them five star boys Pauw! - Tammy from Canton.

This was the first example of the power of collectives, something that I don’t think anyone could have foresaw when the NIL saga started last summer. Are collectives legal? That’s somehwat up for debate. Technically, collectives—as boosters—are free to offer student-athletes money to endorse something (anything besides casinos, adult entertainment, etc.). What exactly some of these guys are endorsing is still to be seen. Because the NCAA provided little to no guidance, schools have continued to push the limits of collectives and NIL. But isn’t that basically pay-for-play in most instances? In my opinion, when propsective student-athletes are engaging in NIL deals before officially signing to a university, whether that be a high school player or transfer, then yes, it is pay-for-play. When its a current student-athlete using a collective to proctor a NIL deal, then its perfectly fine. Players (the term student-athlete is starting to become a bit of a reach for some of these guys) who are going to schools solely because of large NIL deals are invovled in pay-for-play schemes disguised as NIL.

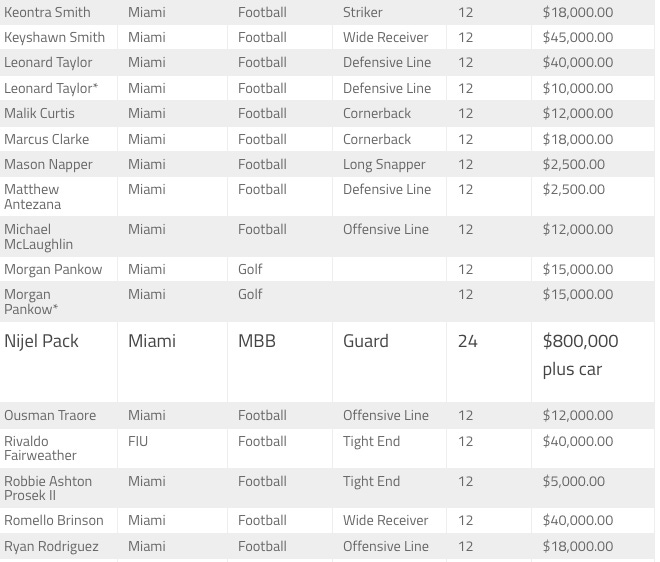

Let’s take Nijel Pack for example. Pack, a standout basketball student-athlete at Kansas St., announced his decision to enter the portal this spring. He committed to Miami on April 23. The very next day, Pack, along with South Florida billionaire John Ruiz (not the boxer) announced a two-year NIL deal worth $800,000. Pack also got a car in the deal. What is Pack endorsing? LifeWallet, “a new, easy to use, and completely safe way to store and access your medical history when you need it the most or to share it with the providers you trust.”

Did Pack go to Miami strictly because of basketball or was it may be due to the massive NIL deal he landed? Probably a mix of both but I would venture a guess that the NIL deal had a large factor into his decision. Is this legal under the current rules? Again, in my opinion, no but it’s very hard to enforce and to be “caught in the act” would be so brazen—and so stupid—that its hard to even imagine a scenario (in this Wild Wild West era of college athletics) where this happens.

Collectives have picked up steam and now every school—and programs at every school—are racing to create collectives. Maybe the University of Miami has just one overarching collective while other schools may have collectives for their football program, another for their basketball program, and now there’s even collectives forming for those non-revenue sports (track and field, volleyball, etc.).

One important thing to note about collectives: they are not all, at a surface level, illegal. Athletic departments—especially coaches—are not allowed to arrange NIL deals for current or prospective student-athletes. Collectives have filled that roled and have helped procotor NIL deals with current student-athletes. Schools like SMU, with their collective, have been proctoring—and publicizing–NIL deals for student-athetes. UTSA alums and boosters have formed a collective, known as Runners Rising Project, which includes a NIL deal tracker.

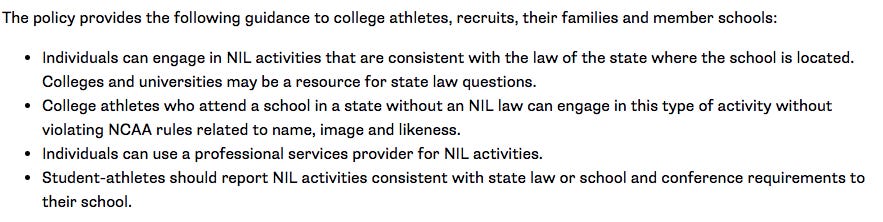

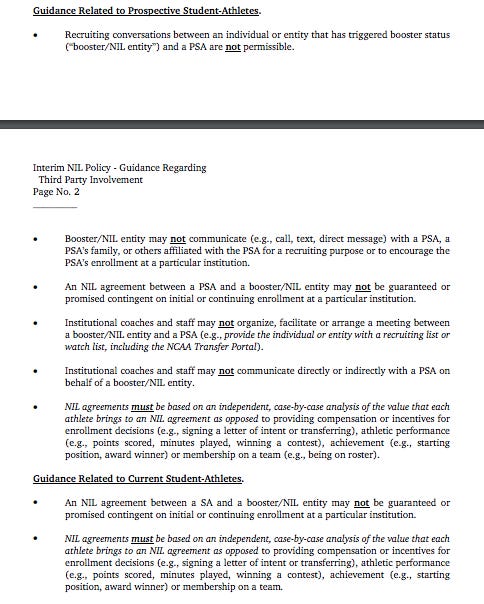

Where things get incredibly murkey is when NIL deals are being used to lure transfers/high school recruits—exactly what Saban was complaining about. The Wichita Eagle has a great article detailing the nitty gritty of this specific part of collectives. The article is currently behind a paywall but the basic premise is that collectives are working hand-in-hand with coaches to bring transfers to their school of choice. The collectives bring a pot of money to the table, and coaches then decide where to spend the money and on who. The collective (individual boosters) then go out and contact the prospective student-athlete and negotiate the deal. The Wichita Eagle documents a scenario in which the coaches and collective work separately but in other situations, the coaches and collectives are likely working hand-in-hand. This is 1,000% pay-for-play disguised as NIL and its not even a secret. The NCAA, in response, provided more NIL “guidance” to institutions.

The guidance above details exactly how the interim NIL rules have been broken over the last 10 months. Rather than guidance they should have labeled this document as “instructions” because if you’re not following these to a T, you are going to be in left behind in the recruiting wars. But why is the NCAA giving out guidance when they should be handing out infractions? I mean haven’t the interim rules very clearly—and publicly—been broken? From what I have read, it seems as though the NCAA is unwilling to “go after” any of these rules violations with any real punishment because they want to avoid further litigation. The prevailing thought is that if the NCAA were to hand out any infractions regarding NIL/collectives that actually threatened the eligbility of a student-athlete, a lawsuit would follow right behind. Rather than another lengthy legal battle—which would be another chink to the NCAA’s already battered public image—they are going to let this NIL chaos play out until Congress steps in and creates federal legislation—or at least that’s what people think is going to happen. There is no timeline for when federal legislation may be passed or even considered.

* Please note: this “article” was dripping with sarcasm. There will be a follow-up ramble in the future where I will take a more focused look at SDSU’s relationship with NIL.