The rumor went something like this:

A long time ago, two small towns were established near the Big Sioux River. They were Aurora and Brookings. One day, someone decided to “pull a prank” and switch the signs. Aurora became Brookings and Brookings became Aurora. Nobody seemed to notice the switch and the towns’ names stayed as they were—despite the name switch.

Now, I’m not sure how true or how real the rumor was but I’ve always had a weird fascination with a) Brookings history and b) how towns get their names. My fascination with Brookings history is simple: I like knowing about stuff, especially when I’ve spent a better part of my life there. The “how towns get their name” fascination is a little different but kind of on that same “I like knowing about stuff” reasoning route. It’s not so much the name itself that interests me but it’s the “why .” Why did the original town’s people decide on one name over another. Some town names are obvious, like Lake Charles, Louisiana, located right next to a “Lake Charles.” Others are not so obvious. Boise, the capital of Idaho, got its name when French-fur traders came upon a river valley, covered in dense overgrowth trees—a stark contrast to the barren high desert that they had been traveling on for days. The story goes that the fur traders shouted “Les boise, les boise” when they saw the valley in the distance. Boise, directly translated in French, means “wooded.” Boise is still known as the “City of Trees” to this day.

Brookings falls directly in the “not so obvious” names category. Through some deep linguistic investigations (aka Google translate), I found that Brookings in German, French and Spanish all mean “Brookings.” Basically this means that the word isn’t listed in those languages and Brookings in Spanish is a direct translation to Brookings in English. But wait, what does Brookings in English mean even? Apparently, not really anything either, other than it is a proper known for a city in South Dakota, a city in Oregon and a Washington D.C. think-tank (the Brookings Institute), named after its founder, Robert S. Brookings.

Like the Brookings Institute, towns are not only named after geographic landmarks, like lakes, rivers, hills, mountains, waterfalls and rapids but also after people. Beresford, South Dakota was, for some reason, named after Lord Charles Beresford, a late 19th century, early 20th century British admiral, who likely never set foot in the town or even the state. Milbank, South Dakota was named in honor of Jeremiah Milbank, a railroad mogul from New York City and a real life, male version of Dagny Taggert.

This is where I came across a man by the name of Wilmot W. Brookings, a prominent judge, pioneer and railroad man from the 19th century. Brookings’ biography is somewhat interesting, despite not being overtly unique for his day.

Here’s a few highlights:

Born October 23, 1830 in Woolwich, Maine

Attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine

Moved to Dakota Territory in 1857 to become a lawyer and then district attorney

In 1858, he was riding a horse from Sioux Falls to Yankton during a blizzard, when his horse fell into a creek. He eventually made it to Yankton but because of frostbite, he ended up having both of his legs amputated from the knees down

He then used “squeaky wooden legs” for the rest of life. Wooden Legs, a craft brew pub in downtown Brookings, is (allegedly) named after Brookings’ replacement legs

Later, he served as Governor of Dakota Territory

Republicans nominated Brookings as a congressional delegate after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination

He was a prominent railroad man, helping to organize the Dakota Southern/Central Railroad

Worked as editor of the Sioux Falls Leader, a newspaper that would merge with the Sioux Falls Argus to form the Argus Leader, currently the state’s largest newspaper

Brookings died in 1905 after a streetcar accident in Boston, Massachusetts

According to a 2013 article in South Dakota Magazine, “Brookings was a highly respected man with huge amounts of courage, energy and ability. These traits led Brookings to be appointed superintendent of a road that was to be built from the Minnesota state line west to the Missouri River about 30 miles north of Ft. Pierre. It was during the construction of this road that Brookings came into contact with land that was part of this county at the time. Because of his drive to settle the Dakota Territory, Brookings County and city were named for a spirited pioneer promoter. Wilmot W. Brookings made settlement of this area real possibility.”

The article refers to a “road” but it is surely referencing the building of a railroad, which was instrumental in the placement of towns across South Dakota, particularly in Brookings County. Towns were surveyed, platted, name and established as a railroad built west. Quite literally, railroad companies were responsible for “designing” most of the Midwest.

In the late 1870s, it was clear that a railroad would be making it’s way into Brookings County. The Dakota Central Branch of the North Western Railroad Company had begun laying rail in Western Minnesota and was planning to bisect the county on its journey west, towards the Missouri River. The only issue was that none of the settlers in the west knew where the rails would be laid in relation to the county. Towns established prior to the railroad being built could be left in isolation if the railroad chose to take a different route and bypass the town. Previously, any settlements that had been established—Medary, Hendricks, Oakwood—had all been near bodies of water.

In 1876, a group of settlers established the town of Fountain, located near a spring (section 2, township 110, range 41) in the northeast half of the county, roughly eight miles away from what is present day Brookings.

You might be asking yourself, “I’ve never heard of Fountain before—does it still exist?”

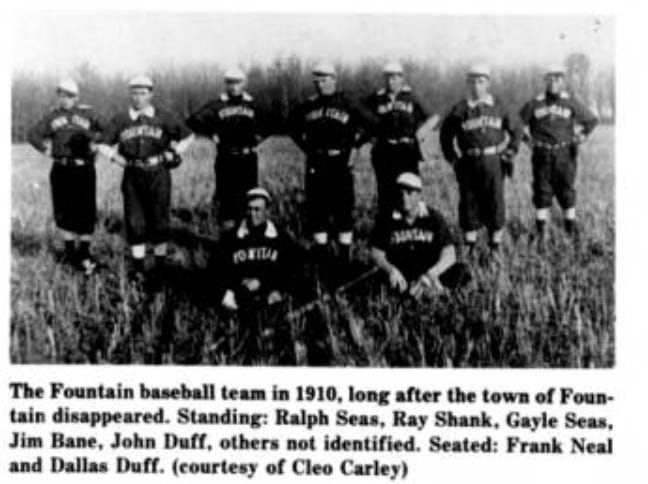

Fountain has been a ghost town for just over 140 years and existed for no more than 3 years. After becoming established in 1876, the town quickly grew, with the construction of a school house, hotel, hardware store and even a baseball team—in large part because of a man named J.O. “Jake” Walker. The hope was that the growth of the town would entice the railroad company to build through it—or at the very least, near it.

As Elkton and Aurora started becoming established in 1879, it was clear that the railroad would be missing Fountain entirely, instead building roughly three miles to the south. During this time—October 3 and 4 to be precise—a town directly west of Aurora was platted and surveyed. The plot of land would go on to become the town of Brookings, named after Wilmot W. Brookings, the grizzly, wooden legged politician turned railroad exectutive who allegedly only visited the area twice. The Brookings County History Book does not mention any other options for the name of the new town, nor does it mention any discussion of any other name than “Brookings.”

Volga was platted and surveyed two weeks after Brookings. Interestingly enough, the Brookings County History Book recalls “there was talk” that the name for the town west of Brookings was up in the air. The options were Terra Coteau, Bandy Town and Bandy but railroad officials ultimately chose Volga. The book theorizes that it may be because railroad officials were trying to bring German-Russians to the area (“Volga” is the name of the longest river in Europe, primarily located in eastern Russia).

The residents of Fountain, obviously, were disappointed by the railroad’s decision to develop an entirely new town, rather than detour to include their recently established settlment. Instead of living in relative isolation, the townspeople—all 25 of them—collectively picked up and moved to Brookings. One man even split his store in half and used horse and ox to drag it all the way to Brookings. The Brookings County Press, a newspaper that operated out of Fountain, closed its doors and reemergemed shortly thereafeter in Brookings. By the end of the 19th century, Fountain was little more than a distant memory.

On Nov. 4, 1879, it was voted that the county seat would move from Medary to Brookings, thus establishing the county governance/set up that we still see today. The reason was primarily geographical—officials wanted the county seat in the center of the county.

Finding Fountain wasn’t as hard as it might have sounded (“Hey, I’m going to try and take picture of an abandonded town from 1879, with no buildings and no real clue where’s it at—shouldn’t be too tough”), even though there wasn’t really anything to find. Going off the description of landmarks (“the city on the hill”), the relative directions (“eight miles northeast of Brookings”), and the original section-township-range, I figure the area where Fountain occupied is somewhere in a two mile by two mile plot of land, now used entirely for corn and cows

Maybe its just me but I’m patial to the name Fountain. I was writing the end of this and trying to figure out how I could argue that, looking back on October of 1879, they should have named the area that would become Brookings, Fountain instead of Brookings. Maybe someone could argue that because all of Fountain’s population moved to populate the new town of Brookings—leaving the old town of Fountain abandonded—they should of just named their new town Fountain, rather than after a railroad executive who (allegedly) only set foot in the town twice. But that’s really not a great argument. What it really boils down to is Fountain is just a better name for a town than Brookings—and there’s nothing even wrong with the name Brookings! Its not a boring name, its actually rather unique—but it doesn’t ring like Fountain. Imagine Fountain, South Dakota, Fountain High School, Fountain Auto Repair, Fountain Public Library, Fountain, home to South Dakota State University , the Fountain Auto Mall, Fountain Municipal Airport.

I’m sold on Fountain. Besides, Wilmot Brookings already has another town in South Dakota named after him.

This was a great read!! As a Lake Charles native, I was way too excited to see it mentioned here. 😆

Great read! I wonder if anyone will ever find archeological evidence of Fountain.