Agents of Chaos

Agents were once outlawed in college athletics. Now, they are the running the show.

Back when the NCAA had a set of enforceable rules — in the pre-NIL days of college athletics — it was driven into student-athletes’ heads that you could not, and should not, speak to a sports agent. This was maybe the biggest “no-no” in all of college athletics. No agents — ever. If you did, you would lose your eligibility and most likely your scholarship.

In 2018, the NCAA cracked the door open for agents to legally interact with student-athletes by loosening their rules. Basically, they realized that men’s college basketball players needed professional guidance when determining if they should, or should not, enter the NBA Draft. Agents were hired in the form of “advisors,” who helped student-athletes with expenses and advice during the draft process.

It was mostly agreed upon this was a thoughtful, sound rule change by the NCAA.

After the Supreme Court’s landmark 2021 ruling in Alston vs. NCAA, student-athletes — not just men’s basketball student-athletes — were suddenly allowed to seek out representation to help secure Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) deals. Under the new rules, all student-athletes could have an agent.

Roughly four years have passed since the landmark ruling and now, agents are causing chaos in men’s college basketball and football, and frustrated coaches are blowing the whistle on the borderline predatory operation.

Independent agents

In early December 2024, Colorado State University’s head football coach Jay Norvell laid out the primary challenges agents present in the world of NIL and the transfer portal. As Norvell explains:

"These independent agents call these schools up that they know have money, and they say, 'You know what, if Kevin gets in the portal, how much would you pay him?" ‘Oh, I'll pay him $150,000,' and they'll go to the next school. 'What if Kevin got in the portal? What would you pay him?' 'Oh, I'd give him 175,' and then another school might say, 'Oh, I'll give them 200,' so now this independent agent DMs Kevin and says, 'Call me. I got some deals for you.' And then they talk, and he goes, 'If you get in the portal, I can get you $200,000 okay? And it's hard for a kid, you know, when he hears that."

Norvell’s example aligns with many other stories stemming from college football and basketball. Say a student-athlete has a great year. People take notice, some of whom may be these “independent agents.” They begin calling up various schools with collectives, basically shopping the student-athlete around to the highest bidder. Often, these student-athletes don’t even know they are being shopped. In the situation that Norvell describes, the student-athlete does not even have a prior relationship with the agent — the “DM” (often) comes out of nowhere.

When the independent agent finds the highest bidder, they reach out to the student-athlete through social media and inform him of the offer.

“You can make $200,000 from (x school) if you get in the transfer portal.”

The student-athlete may not even be considering the transfer portal but the lure of money is real. For most people, $200,000 is life-changing money. How could you pass it up?

Over 3,000 Division 1 football student-athletes entered the transfer portal during the 2024-25 cycle. How many of these independent agents enticed them into the portal? How many shopped them behind the scenes? Hard to say but Norvell said that his top 25 players were all contacted with “substantial offers.” It’s fair to assume at least some chunk of the 3,000 were enticed by these independent agents.

But what is the motivation for these independent agents? Are they doing this to help student-athletes capitalize on “NIL” opportunities? Doubtful.

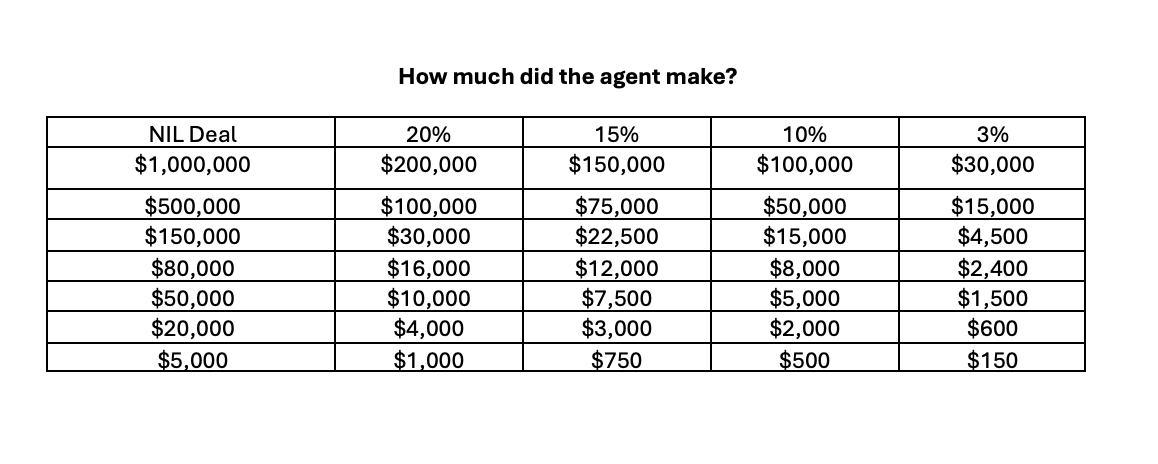

What’s really happening is simple: these independent agents are capitalizing on a lawless, unregulated market. See, what’s just been coming to light over the past year or so is the exorbitant — almost criminal — percentage agents are taking from these NIL deals. According to a few different reports, these agents take around a 10-20% cut. Compare that to an agent in professional sports, where the average take is around 3%.

On top of this, many of these independent agents are not certified and have no formal experience being an agent. Some rules exist that say agents must be certified with the state they are operating in but those rules are rarely enforced. The NCAA also has no teeth to enforce any rules related to NIL. These “agents” are more or less free to operate in this highly lucrative — and lawless — market and are profiting off the backs of student-athletes. Highly predatory behavior, to say the least.

“I have seen so many people call themselves NCAA-certified even though the NCAA doesn’t certify NIL agents,” said Darren Heitner, a Florida-based sports and entertainment lawyer who specializes in NIL. “Everyone likes to say that NIL transactions and athletes finally getting their due is the wild, wild west. Well if you want to talk about the wild west, it’s the agent piece that’s ground zero for that, because so many of them are ignoring the actual laws. And in the past few years, I haven’t heard one story about a state’s attorney general or secretary of state coming down on an NIL agent for not being properly registered.”

“Talk to my agent” — anonymous transfer portal regular

Personnel staffer 1: Some of them are highly qualified agents who are reputable and have history and background of success within the world. Then you have this other group of agents who have no f—ing clue what they’re doing. They’re just latching on. A kid hits the portal and all these agents are just sharks DMing them. These kids are like, “My buddy got an agent and made $100,000 — I should get one too.” So they get this agent on Twitter and this guy has no idea what he’s talking about and is asking for 10, 15, 20 percent of the contract when the NFL maximum is 3 percent.

Head coach 2: I had a player commit to me, to my face, on a visit. And I asked if we needed to talk business, and the player said, “No, I’m good, just talk to my agent.” And the agent was out of this world, saying it would cost $800,000 to $1.2 million. OK, well, sorry, we’re out. Is the kid really going to get that money? I don’t know. But he’s not coming here now.

Profit motivated

The problem isn’t just independent agents shopping prospective portal players. It’s also “licensed” agents looking to maximize their own profits. The most glaring case of these types of profit-motivated agents comes from the Leon Lowery situation, outlined in this December 2023 article from the Athletic.

The story goes like this: Lowery enters the transfer portal and takes a visit to the University of Wisconsin. Everything is going well and Lowery commits to Wisconsin at the end of his visit. He then returns home and suddenly de-commits without informing the Wisconsin coaching staff. Instead, he posts a cryptic message on social media — “Stand on what you believe in and know your worth” — and directs all future inquires to his two new agents, both of whom were not present nor discussed on the Wisconsin visit.

Cipot (Lowery’s high school coach) said very little of the discussion with (the Wisconsin) coaches was about NIL because Lowery was invested in being developed as a football player and liked the fit of the program. But everything changed Monday.

“Somewhere, somehow, an agent sneaked into Leon’s life,” Cipot said. “When all that stuff went down on Monday, it didn’t seem like it was coming from Leon.”

….

One hour and 41 minutes after the phone conversation with Wilson (Lowery’s agent) was over, Lowery tweeted: “From this moment on I’ll be handling all of my recruitment personally.” Lowery had fired his agents late Tuesday afternoon. Lowery did not respond Thursday to a follow-up voicemail message request for comment.

When Cipot said he was finally able to talk to Lowery, he was told that the agents were asking for a 10 percent cut of any NIL earnings Lowery might make. (For comparison, NFL agents receive up to 3 percent commission on NFL deals.) He also said Lowery told him the agents were insistent that Wisconsin’s staff wasn’t telling the truth about its goals for Lowery to graduate or play, which Cipot adamantly disagreed with, as he was there on the official visit. He noted money was never a driving factor for Lowery.

“He was trying to tell me the agent was pulling a fast one on him and he fired him that night,” Cipot said. “I think they were looking for a bigger deal so they could get paid. That’s what I took out of it. Obviously, they weren’t in it for the interest of the kid because the kid wanted to go to Wisconsin. He was whole-heartedly all-in.”

This is the unfortunate reality of college athletics. Agents, motivated by profit, are causing student-athletes to reconsider what they believe to be their best option, solely for their own self-interests. This hurts the student-athletes and the university. The only ones who aren’t hurting in the NIL-era? Agents.

The Sluka case

Another consideration with NIL deals is the informal nature in which they are done. The Matthew Sluka case from last fall is “Example A” of the multifaceted problems that can arise from the informal, unregulated world of NIL deals.

Matthew Sluka had a solid four-year run as quarterback of the Holy Cross Crusaders. In perhaps his best game, he rushed for over 200 yards in a FCS semifinal loss against the South Dakota State University Jackrabbits in 2022.

Following the 2023 season, Sluka entered the transfer portal. He committed to the University of Nevada-Las Vegas in January 2024.

After leading UNLV to a 3-0 start this past fall, Sluka announced on social media that he would be redshirting the rest of the season and entering the transfer portal. This sudden and unexpected announcement took everyone by surprise.

On X, the everything app, Sluka wrote:

"I have decided to utilize my redshirt year and will not be playing in any additional games this season. I committed to UNLV based on certain representations that were made to me, which were not upheld after I enrolled. Despite discussions, it became clear that these commitments would not be fulfilled in the future. I wish my teammates the best of luck this season and hope for the continued success of the program."

Sluka claims he was verbally offered $100,000 by a UNLV assistant coach to come play for the Rebels during the recruiting process. According to Sluka, his agent and his father, he only received $3,000 to help relocate to Las Vegas. But UNLV donors say there was no $100,000 NIL deal in place. In fact, they say they agreed to just $3,000. After making repeated inquires into the status of the deal, Sluka eventually missed practice and then announced his departure.

With no written offer or contract, this was a complete “he said, she said” situation. Sluka said he was offered $100,000 while UNLV says Sluka’s agent made “financial demands to the school in order to continue playing.” UNLV later came back and said that assistant coaches do not have the authority to verbally offer NIL deals (an admission that there was a $100,000 offer at some point?). UNLV also said that “it does not engage in such (pay-for-play) activities, nor does it respond to implied threats.”

On top of all this, Sluka’s agent, former Wisconsin cornerback Marcus Cromartie who allegedly brokered the NIL deal, is unregistered and unlicensed in the state of Nevada.

Sluka left the team after one of the best starts in Rebel Football history and leveraged the NCAA’s redshirt rules to retain his eligibility for an additional season. He entered the transfer portal in September and in January, committed to play for his former coach at James Madison University. He will have one year of eligibility remaining.

UNLV finished the season 11-3 and after losing to Boise State in the Mountain West Championship, defeated the University of California, Berkeley in the “Art of Sport LA Bowl Hosted by Gronk.”

What’s next?

In April, the House vs. NCAA settlement is expected to be finalized and approved which will allow for schools to pay athletes directly through the revenue-sharing model. This will likely require student-athletes to enter into formal contracts with the school. A recent situation at the University of Wisconsin gave us our first preview for what’s likely to come.

Read more on the changes shaping college athletics from Observations from the Cheap Seats

But what role will agents play in these contracts? That is unclear at the moment. Will schools be working with each individual agent to develop the contracts? That will likely depend on how much negotiating there is to be done. From my perspective, that seems like an extremely large amount of legwork and manpower from the university side to negotiate revenue-sharing contracts with each student-athlete’s agent but maybe thats what will have to be done.

Agents will continue to facilitate NIL deals when available but those may be few and far between as schools will likely purchase a student-athlete’s full NIL, potentially eliminating third-party deals. My guess is that agents will begin looking closer at the high school ranks to sign players before they even step foot on campus.

In the mean time, there are plenty of ideas on how to clean up this mess with rules and regulations. Some of those include an official agent database or a disclosure form for when agents are not registered or licensed. A seemingly obvious solution would be a certification process for agents. But even with these ideas, it comes back to one question: Who is going to enforce the rules?

It appears the solution — unfortunately — lies with Congress. Until actual laws are put in place that either regulates the entire NIL system or allows the NCAA to enforce its rules without the threat of endless antitrust lawsuits, we can expect this madness to continue.

Recently, Axios reported that Cruz is expected to hold NIL hearings now that he chairs the Senate Commerce Committee. Cruz had previously introduced a college athletics bill in 2023, but it went nowhere. Now that Republicans have a trifecta, there seems to be far more appetite for bipartisan support to get a bill passed. Reading the tea leaves, I would expect a hearing on this issue at some point this spring.

Cruz outlined some of the ideas that might be addressed at this hearing on his podcast, “Verdict with Ted Cruz” (via Sportico):

Establish a national NIL standard

Provide the NCAA an antitrust exemption

Declare that college athletes are not employees of their universities

While it’s hard to say if a bill that includes the aforementioned points would “save” college athletics, it would go a long way — at the very least — in stabilizing college athletics in a meaningful way.

I have begun to irregularly post “notes” (Substack’s version of a long form tweet) on various topics (college athletics, history, running, music, etc.) here.